Bessel van der Kolk is a psychiatrist (license no. 33726) and author based in Boston, Massachusetts. Most of his work focuses on post-traumatic stress disorder. He is best known as the author of The Body Keeps the Score,[1] a pop psych book that promotes the pseudoscience of repressed memories. Van der Kolk champions so-called “body memories,” a variant of repressed memory pseudoscience that alleges memories — particularly traumatic memories — can be stored in the body rather than the brain.[2] Van der Kolk further argues that memories for overwhelming traumatic events are stored in pristine condition on a perceptual level (for example as sights, smells, and sounds); only once these perceptions are “translated” into a narrative account of the trauma is the possibility of false memory introduced, according to van der Kolk.[2] He has expressed mixed views regarding the existence of Satanic ritual abuse.

Background

Van der Kolk was born in the Netherlands. He graduated from the University of Hawaii in 1965 with a degree in political science and pre-med. He obtained an M.D. from the University of Chicago in 1970 and was a medical intern at Queens Medical Center in Hawaii from 1970-1971. In 1974 he completed his psychiatric residency at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center, affiliated with Harvard Medical School.[3] According to Wikipedia, van der Kolk then became Director of Boston State Hospital, after which he was a staff psychiatrist at the Boston VA Outpatient Clinic.[4]

In 1982 he co-founded the Trauma Research Foundation (previously known as the Trauma Center), where he remained Director until he became the Research and Medical Director in 2000. From 1992-1997 he was an Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He has been a Professor of Psychiatry at Boston University School of Medicine since 1996. From 1997-1999 he was a Professor at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education. From 2008-2016 he was Vice President of Research at the Justice Resource Institute, and from 2012-2017 he was Co-Director of the Complex Trauma Treatment Network of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.[3]

Van der Kolk’s work focuses on trauma as well as its effects on the body and development. He has undertaken research relating to EMDR, neurofeedback, yoga, and MDMA.[5] He published The Body Keeps the Score in 2015.[1]

Van der Kolk is a regular speaker at annual conferences of the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (ISSTD), and has received awards from the organization.[citation needed] Van der Kolk is regularly featured in webinars on trauma, stress, and healing.

Role in the Satanic Panic

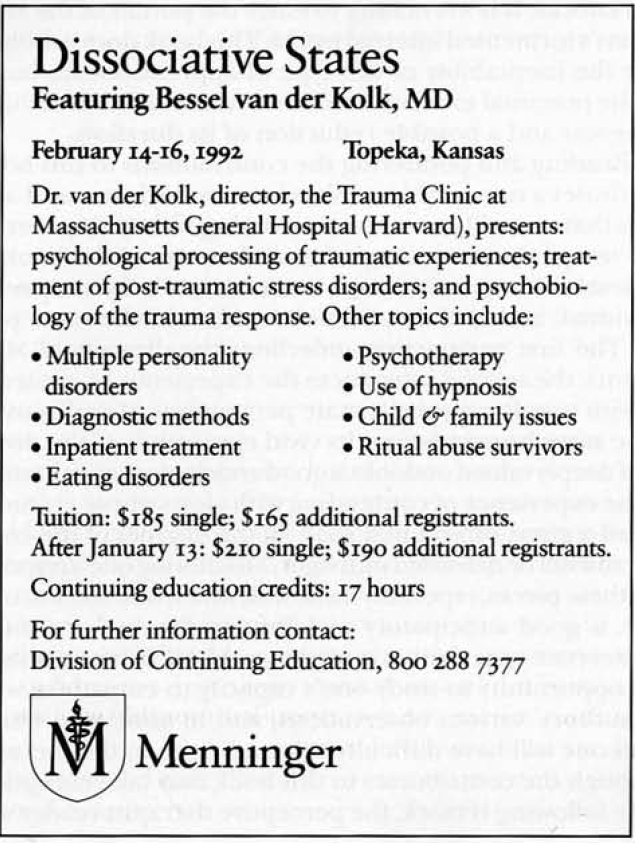

Van der Kolk is the most prominent of the conspiracy therapists, though he typically avoids directly promoting conspiracy theories of Satanic ritual abuse. Instead, in his books, presentations, testimony, and popular media appearances, van der Kolk criticises those who doubt the veracity of recovered memories. As such, van der Kolk is the type of conspiracy therapist that covers for promoters of Satanic ritual abuse while generally refusing to publicly comment on the topic himself. However, it should be noted that van der Kolk held a presentation in February 1992 that involved the topics of hypnosis and ritual abuse, an advertisement for which was published in the ISSTD‘s Dissociation journal.[6]

Van der Kolk was on the editorial board of Dissociation from its first issue in March 1988 through its last issue in December 1997.[7][8] The journal published numerous articles promoting the Satanic ritual abuse conspiracy theory.

Van der Kolk believes that memories of traumatic events “may be stored as somatic sensations, behavioral enactments, nightmares, and flashbacks.”[9] He regularly serves as an expert witness in trials, unfailingly testifying in favor of the pseudoscience of repressed memories. According to RC Barden, a scientist, clinical psychologist and attorney who deposed van der Kolk, he ceased serving as an expert witness on multiple cases following a deposition in which Barden revealed van der Kolk’s “shocking ignorance of his own profession.”[10]

Discussing van der Kolk’s concept of so-called “body memories” — implicit memories of trauma exhibited via bodily expressions but lacking in narrative content — Harvard University Professor of Psychology Richard McNally writes:

[T]his line of mistaken reasoning inspired so-called “recovered memory therapy,” arguably the most serious catastrophe to strike the mental health field since the lobotomy era. […] There is no convincing evidence that trauma survivors exhibit implicit memories of trauma, such as psychophysiologic reactivity, without also experiencing explicit memories of the horrific event as well. Thus, even when the body does “keep the score,” so does the mind.[11]

Misconduct

In 1995, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)[12] and Harvard Medical School[10] launched investigations into Danya Vardi, a research associate working for van der Kolk, for scientific misconduct. Vardi was accused of falsifying data meant to be collected from research participants pursuant to a study funded by an HHS grant; she was later found guilty.[13][10] Although van der Kolk claimed to have been “aware of” Vardi’s falsification of data “from the very beginning,”[10] he acknowledges Vardi’s contributions in the form of data collection in at least one published paper[14] and discussed Vardi’s work in glowing terms.[15] The paper, originally titled “Dissociation and the Perceptual Nature of Traumatic Memories: Background and Experimental Confirmation” and submitted by van der Kolk as part of his expert testimony in the Hungerford case,[16] initially included Vardi as a coauthor. The title was later modified to “Dissociation and the Fragmentary Nature of Traumatic Memories: Overview and Exploratory Study,” with Vardi no longer listed as a coathor.[10] The original paper claimed that 77% of participants provided the researchers information confirming their traumatic memories and reported that the group of participants first traumatized as adults scored higher than the mean of the overall sample on the Dissociative Experiences Scale. However, the revised version of the paper indicated that participants self-reported that they had corroborated their traumatic memories. In addition, the statement comparing Dissociative Experiences Scale scores between groups was deleted, which van der Kolk claimed “may or may not have been” because it was contrary to their hypothesis.[17](p. 360-364)

In 1997, van der Kolk repeatedly refused to comply with a subpoena in a case in which he was listed by the plaintiff as an expert witness, to the extent that the judge granted the defense’s motion to bar him from providing testimony.[18] Van der Kolk also refused to testify in a separate 1997 case. He allegedly called the plaintiff, claimed he was being harassed by the False Memory Syndrome Foundation, and urged the plaintiff to drop her case. According to a lawsuit that plaintiff filed against van der Kolk in 2004 as a result of his refusal to testify, van der Kolk left a message, stating, in part: “[Y]ou must realize that if your case comes to trial I will not testify for you. That is not something you can bargain about and I think without my testimony you will probably not win, but as it stands now with my testimony you would not win either, because of certain legal maneuvers that are too complicated to tell you about. So, I urge you very strongly to take the advice of your attorney. This is not the time to be stubborn or to think that you know better than anybody else. […] I am no longer on your case. I cannot explain this to you. Don’t call me back. Pay your bill. You don’t do anybody a favor by being headstrong about it.”[19] According to the complaint, the plaintiff was forced to drop her case due to van der Kolk’s refusal to testify. Van der Kolk later testified that the lawsuit filed against him was dismissed.[20](p. 7-12)

A complaint filed in 2007 with the Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine details disturbing allegations against van der Kolk by a former patient.[21] The complainant alleged that van der Kolk diagnosed her with PTSD, and that, together, “we’d soon learn that a series of traumatic events which I survived in 2000 where [sic] the root of my problems,” including being “abducted and held captive by individuals who committed multiple felonies, including numerous murders.” The former patient expresses gratitude for van der Kolk’s apparent help in recovering these memories. However, once the patient began to get back on her feet, finish school and land a job, van der Kolk allegedly “took resentment to my rapid and independent success.” The patient, seeking closure, was planning to petition the police to open an investigation when van der Kolk allegedly introduced her to a woman (and then-current patient of his) from the Massachusetts Office for Victim Assistance and an active police officer (and then-former patient of his) who was also a private investigator. An odd dynamic ensued, according to the complainant, in which van der Kolk allegedly insisted the private investigator charge her more for his services, and all communication between the three parties go through him. Moreover, van der Kolk seemed to be discouraging the patient from reporting the alleged crimes to police in Arizona, offering “horrifying portrayals of impending doom” should the patient do so. From there, the complainant details how her relationship with van der Kolk fell apart, eventually ending in her sudden termination from therapy. It appears that van der Kolk’s distancing from her came about as a result of her intentions to go to the police in Arizona, presumably where the alleged abuse took place. The complainant re-enrolled in therapy at Justice Resource Institute (the parent company of the Trauma Center, now known as the Trauma Research Foundation) with a different therapist, in preparation for the anticipated investigation into her allegations of abuse in Arizona. Despite the fact that she insisted that van der Kolk not be involved, she alleges that he was closely supervising her new therapist’s interactions with her. In response to these allegations, van der Kolk claimed to have been skeptical of his former patient’s recovered memories, contradicting the complainant’s assertion that van der Kolk assisted her in recovering them.

Van der Kolk submitted expert testimony in the 2015 trial of Gigi Jordan, a severely mentally ill multimillionaire Manhattan socialite who murdered her eight-year-old autistic son, Jude Mirra, in a “mercy killing” meant to save him from a Satanic cult conspiracy.[22] Van der Kolk’s testimony intended to describe how trauma could allegedly manifest in symptoms consistent with autism, but it was excluded on procedural grounds.[citation needed]

Van der Kolk was terminated from the Justice Resource Institute in 2017 following allegations that he created a hostile environment that permitted abuse by the then Executive Director of the Trauma Center.[23] Van der Kolk sued the Justice Resource Institute and the matter was quickly settled out of court.[24] According to Wikipedia, in 2018 he founded the Trauma Research Foundation with the money provided by the settlement.[4]

Q: Do you believe Satanic ritual abuse occurs in this country?

A: Unfortunately it does.[25]

A child who is abused is likely to suffer from one of the 10 leading causes of death.[26]

Q: Now, this transcription [of traumatic memories from perceptual information into narrative form], is it possible for that transcription to be interfered with from external sources?

A: I think it’s quite possible for people-

Q: Yeah-

A: Yeah.

Q: -let me just give you an example. Many times with kids where kids have been abused we hear complaint about leading questions.

A: Yeah.

Q: Do you believe that putting an individual into a state where they are – where they will easily succumb to suggestion assists in interfering with transcription of those perceptions-

A: Oh, yeah.

Q: -perceptions into memories? Is that a Yes?

A: Oh, yes.

Q: So that you would have a problem, then, if something such as hypnosis were used to transcribe perceptions into a narrative?

A: No, I would have no problem with that.[16](p. 21-22)

Q: Are you aware of any new information regarding this area of whether memory repression actually exists that’s come up since the last time we spoke?

A: Nobody’s interested in the question whether it exists. The question is how does it work? Everybody knows it exists.[16](p. 43)

Q: The two doctors that you’re speaking about from Harvard, was their study about the effects of the sodium amytal, or did they use it for some other research purpose?

A: I think that their paper was used to describe when you do a sodium amytal interview, but when Christianson and I did research together, he talked about it from time to time, and he used to tell me what remarkable clarity people were sometimes able to remember things that they had forgotten, adult traumatic incidents, and-

Q: He’s talking about the clarity of the way they describe something?

A: Yeah, yeah.

Q: Okay. Does his research-

A: So there’s a clinical experience.

Q: Okay. But does his research indicate that the very clear description that’s given in any way is a reliable indicator of what actually happened?

A: See, the trouble is we weren’t there, and when people say, “this is what happened to me in Vietnam, and I see it,” and they say, “I see that’s exactly where it was,” I say you were there and I wasn’t.[16](p. 47-48)

Q: Well, do you agree in psychiatry that process of reexamination happens quite a bit?

A: Yeah, yeah-

Q: For instance, you’re familiar that-

A: Focus shifts all the time.

Q: You’re familiar that schizophrenia at one time was thought to be caused by children’s mothers?

A: Is that not true?

Q: Well, isn’t – since that theory has been around, that’s been changed; isn’t that correct?

A: Well, I think this schizophrenia, people still don’t know where it comes from.

Q: Has the field of psychiatry disabused itself of the idea that schizophrenia is caused by your mother?

A: Currently psychiatry has the opinion that schizophrenia is an illness, but the proof for that is not really that great.[16](p. 68-69)

There’s another group of people who are very controversial in the field, I’m not that involved in it, and that’s the whole issue of Satanic ritual abuse. […] I’m evaluating these adolescents right now who were ritualistically abused, and the grandfather was actually put into jail, and that’s the case, and they know about the rituals that they went through. So these things happen. But there are a group of patients who I happen to hardly ever have seen, I’ve seen one or two of them who claim that they are part of a large international sexually abused ring, and the stories are consistent of eating babies and sacrifices, et cetera. And on the one hand it sounds like Jonestown, which really did happen. On the other hand, I don’t know that that happens to the frequency and extent that these patients claim.[16](p. 77-78)

Q: We had spoken a little bit before we had taken that recess about reliable memories of traumatic abuse, and you had listed three things that you look at – and please correct me if I’m stating that wrong – about how you make a determination of whether or not a memory is reliable, and they were – the first was corroboratory evidence, the second one internal consistency and the third was physiological states?

A: Uh-huh. Right, right, although I would actually put corroborative evidence last here.[16](p. 90)

Q: Are you aware of situations that have occurred where people have claimed to have recovered memories of prior sexual abuse or trauma and have then determined that, in fact, those memories were not true?

A: Yes.

Q: Are you familiar with that?

A: In fact, about half of my patients around Thanksgiving stop believing that their traumas actually happened.

Q: They stop believing?

A: Yeah. Christmas time, Thanksgiving time all my patients say, “I want to go home. I want to have a family.” And all of my patients, almost – a very large proportion of my patients at that point say, “I must be making that up.”[16](p. 118)

Q: I mean, clearly [some patients] will come in and say that they have a mental image of a baby being taken out of their womb and eaten or blood being drank?

A: No, no. See, that’s interesting. These Satanic stories are just that, stories.

Q: Because someone tells you a Satanic ritual abuse incident, you say it’s a story. Why can’t they come before you and tell you about a rape and it also is a story, a run of the mill rape is such a horrible thing?

A: They can. There are plenty of people that can tell me a story about a rape, particularly after a treatment, after a while. They’ll say, “Last year October 25th I was raped in the Northeastern University parking lot,” and they’ll tell me a story about it.

Q: And it may be true or may not be true?

A: I doubt anybody would come in and tell me the story for the hell of it.

Q: Why would someone come in and tell you about a Satanic ritual?

A: Because they’re haunted about feeling bad.

Q: Why can’t that person who’s haunted about feeling bad come up with a sexual abuse story which is not ritual abuse?

A: I don’t have answers to that. I don’t know about ritual abuse because listening to it, I’m very skeptical about it. What fascinates me about that and the UFO story is the consistency of it which makes me almost believe that Jung, who I don’t even have any respect for as a scientist, that there are certain archetypal ways of organizing experience, right?

Q: Is it fair to say that you don’t have, in your own opinion, a satisfactory answer to that question?

A: It’s also-

Q: I’m sorry?

A: It’s not a very important question for me.

Q: For you?

A: No.[16](p. 151-153)

I mean, all of these crazy people send me their books because I’m one of their heroes. I get to see all these crazy books that believe in the Satanic ritual abuse. I know.[16](p. 154)

Q: Of the people that you have seen in your practice who claim to have repressed memory, what percentage of those did you conclude did not have a repressed memory?

A: That’s just — I have been involved in some forensic cases where I thought people were trying to manipulate the system by claiming a repressed memory. Trying to — in clinical practice you really don’t see false memories particularly.

Q: Why is that?

A: Why would people make up nonsense stories? It’s not fun to have memories of sexual abuse. These are memories that people hate to have. So it’s not something that people voluntarily create because it’s fun or interesting.

Q: Do you do anything in your clinical practice to try to corroborate whether somebody who claims a repressed memory [sic]?

A: Why would I do that?[20](p. 34)

Q: What studies exist where they have studied victims of trauma where the studies indicate that the victims do not repress memories?

A: There are none.

Q: No studies at all?

A: No. There has never been a study of sexually abused people where people have not found a percentage of people repressing their memory.[20](p. 91)

Q: I’m looking for the contrary studies that you are aware of.

A: A contrary study that shows people don’t repress traumatic memory?

Q: Correct.

A: There are no such studies. They don’t exist.

Q: There are no studies adverse to the Williams study?

A: No. There’s no prospective study of sexually abused people that shows that they don’t repress their memory. It doesn’t exist. I have never heard of it.

Q: How about in general what are the strongest studies that indicate that victims of trauma, whatever type of trauma that is, do not suffer repressed memories?

A: There are no such things.

Q: No studies at all?

A: No.[20](p. 104-105)

Q: [Statement from] [t]he American Medical Association Council on Scientific Affairs [Report on] Memory of Childhood Sexual Abuse 1994: “The AMA considers recovered memories of childhood sexual abuse to be of uncertain authenticity which should be subject to external verification.”

A: That’s their statement. I don’t agree with that, but they are entitled to that.

Q: You are aware of that statement from the AMA?

A: I’m aware of it. Uh-huh. I think it’s important to note only half the burden of proof be on the victims. I think the burden of proof is also on the perpetrators.[20](p. 108-109)

Q: Are you aware of the paper Custer’s Last Stand?

A: Custer’s Last Stand?

Q: Correct.

A: No.

Q: You have not read that paper?

A: No.

Q: Earlier you mentioned the Brown, Scheflin, and Whitfield paper?

A: Book.

Q: Book. Sorry.

A: Book of the year for the Society for Psychiatry and the Law.

Q: Brown, Scheflin, and Whitfield has an article in the Journal of Psychiatry and Law, correct?

A: Right.

Q: Then there was Custer’s Last Stand was a criticism of that article?

A: No.

Q: You don’t know?

A: I don’t read the perpetrator lobby literature. If they have data, I read the data.[20](p. 118-119)

[In response to questions in a deposition about Vardi’s scientific misconduct:] It is a perpetrating maneuver. I hate to be perpetrated. You are inserting yourself into my laboratory. It is off limits. It’s like sexual abuse. It is off limits. My scientific data are my scientific data. It is between me and my scientific peers. It’s off limits to you just like the body of children is off limits to adults. Okay?[20](p. 146)

What Kardiner says is that these traumatized people, in this case combat soldiers, develop physioneurosis. That means that their bodies change, and their bodies stay on constant alert for the return of the trauma. They are always ready to be traumatized again. And he says amnesia is a very central part of it. And the more people do not remember, the more messed up they are, the more symptomatic they are.[27](p. 30)

Q: Why is [repressed memory] controversial as it is placed to sexual abuse?

[…]

A: My opinion is that it is too horrible to contemplate that these things happen. You know, in our clinic, we see lots and lots of kids with confirmed sexual abuse, and every story makes you sick. And every story makes you think that life just doesn’t make any sense at all. And I think all of us like to live in a world in which these things don’t occur, and we’d like to deny the reality of what’s being done to children. I think that’s a large part of it.[27](p. 43-44)

[A]s long as these memories are outside of conscious awareness, the mind cannot mess with them. As ordinary memory researchers have shown, memory is a very flexible and malleable phenomenon so that once you are aware of something, your mind keeps changing things. But in a way these repressed memories, these dissociative memories, are like Egyptian — like in sarcophagi, buried underground, and as long as no air can get to them, other information cannot get in there to contaminate them.[27](p. 56)

Q: For those of us outside of psychiatry — I’d like — well, I’d like to ask about two layman’s terms that we have heard in this courtroom: One is “kook” and one is “crazy.” Do those — is [plaintiff] crazy, is she a kook?

A: Certainly not.

Q: Are those words that mean anything in Boston?

A: My close friends call me a kook sometimes.[27](p. 73-74)

These were 15 women with confirmed histories of sexual abuse as young girls. And we tested their immune system, their capacity to fight infections and how their bodies dealt with external things that needed to be taken care of. And what we found is that even — that they had abnormalities of immune cells that are known as the memory cells. And that means that in the immune system there are certain cells that are set to remember whether something is safe or dangerous. And it turned out that in sexually abused women, their immune cells were set to remember that what was coming in was sort of danger, and they overresponded to incoming input, which our reserach showed made them liable or vulnerable to develop autoimmune diseases.[27](p. 81)

And so, when I — when I now do an evaluation of traumatized people, what I ask them is: “Tell me what you see. Tell me what you smell. Tell me what you feel in your body.” Because that is really where the memories are stored.[27](p. 97)

Q: Based on your review of [plaintiff], did you find symptoms consistent with what the studies show as to the effects of early childhood sexual abuse?

A: There were a number of features of her that we — stood out. For one thing, on interviewing her, she struck me as one of the brightest people I have had the pleasure of interviewing. And I was certainly amazed that she had a grade point average of 0.4, at one point while she was an adolescent in school performance. That is so way below her intellectual capacities that you wonder what is interfering with her capacity to study at that point. So her intellectual performance was way below what you would have expected. The other thing that’s very striking, of course, is how grossly overweight she was for many years. And she almost made a spectacle out of herself by being quite a gross person in the U.S.[27](p. 122-123)

Q: Is there any scientific literature, any studies that you are aware of that have been done that show that asking a question with one hand and answering the question with the non-dominant hand is a mechanism by which you can recover an accurate memory of the past? Are there studies?

A: It’s interesting that you ask the question, actually, because this great Frenchman who knew more about trauma than anybody else, Pierre Janet, who I mentioned this morning, in 1889 in his book, L’Automatisme Psychologique, which is the best book about trauma until that one, actually wrote about that very phenomenon.

[…]

Q: Did Mr. Janet […] do any research to determine the accuracy of the memory that was recovered using his technique in the 1800s?

A: He found it to be very effective.

Q: He found it to be very effective. I am asking a different question, though. Did he find it to be a reliable source for the recovery of memories?

A: I don’t think he was ever asked to testify in court about whether these memories were true or not.

Q: Well, that doesn’t seem to me to be responsive to my question. Did he attempt to ascertain whether or not the memory recovered through this technique was a reliable tool for [recovering memories]?

[…]

A: No, he didn’t.

Q: Thank you. And are you aware of a single study as of 1996 that has validated this as a reliable technique for recovering memory, Doctor?

A: Not to my knowledge.[27](p. 135-137)

Q: Do you agree, Doctor, that the recovered memories controversy is a debate about accuracy, about distortion, about suggestibility in memory?

A: I’m not sure what the debate is about. I sometimes wonder if it is a debate between pedophiles and the people who actually treat traumatized patients.[27](p. 154)

I have seen a total of two people out of the hundreds of people I’ve seen who were Satanically ritually abused.[27](p. 170)

A: I deal with very small children who have these incredibly accurate memories.

Q: Memories that include conversations from age three?

A: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Q: How do you tell the difference between a memory and confabulation? There isn’t any way, is there?

A: Well, you know, it is very hard to make up these things.[27](p. 220)

Q: So do you believe that it is a scientifically proven, tried and true technique to establish the age of someone in a memory by asking the emotional Ouija board, “C.C., how old are you?” And saying, “Are you eight”?

A: Uh-huh.[27](p. 230-231)

I don’t know what “junk science” means.[27](p. 242)

Q: Is it your professional opinion that the Rorschach test has been shown to be a valid and reliable psychological instrument?

A: Indeed I do.[17](p. 71)

Q: Do you believe that there are intergenerational Satanic cults involved in human sacrifices operating throughout the United States and have been operating for hundreds of years?

A: I don’t know, I’ve seen some survivors of Georgetown, and I know that — and some survivors of concentration camps, and I know that people are capable of doing unspeakably horrible things to each other.[17](p. 81)

Q: It mentions here that all of the subjects, regardless of age at which the first trauma occurred, reported that they initially “remembered” the trauma in the form of somatosensory or emotional flashback experiences.

A: That’s correct.

Q: So that’s something you find to be a strikingly high percentage of the patients.

A: A hundred percent is strikingly high, yeah.[17](p. 96-97)

Q: Is there any literature on people having false memories of this type?

A: As you know, very poor. There’s really hardly anything on that side of people making up stuff.

Q: Have you ever seen any case examples of that?

A: Oh, yeah, sure, I have, but —

Q: Of people having, you know, just very detailed elaborate false memories.

A: Yeah, I have, yeah.

Q: Right.

A: But, as you know, there’s virtually no literature on that.

Q: Except for the huge literature on people like Dr. [Bennett] Braun who believe these things to be true, right?

A: Yeah, But nobody’s ever studied any of those, so we don’t know. You know, I haven’t seen his cases; nobody’s seen his cases. Maybe all the people in the world who have been Satanically abused all find a way to Dr. Braun’s door, and if you investigate it, that you’d find all the stories to be true. I don’t know.[17](p. 99)

Q: With this new treatment outcome research, what kinds of, what informed consent process do you go through with your patients?

A: I know that’s an important thing for you. I think we don’t do informed consents with patients, by and large. It is not yet a standard of care as I know it.

Q: Are there any legal or statutory obligations–. Now, I’m not asking you for your legal opinion, I’m asking you for your medical opinion. Are there legal or statutory obligations on you as a psychiatrist with regard to informed consent in practicing in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts at present?

A: Actually, I’m not aware of them.

Q: Are you aware of the Nuremburg Codes?

A: I know of the Nuremberg trials.

Q: But —

A: I don’t tend to lump myself together with those guys in the dockets in Nuremburg.

Q: Well, are you aware of any international biomedical ethical rules that were promulgated as the Nuremburg Codes shortly after the Nuremberg trials?

A: Only in the vaguest sense, in the most general sense, yeah.[17](p. 153-154)

Q: What’s your understanding of the scientific term “confirmatory bias”?

A: I wouldn’t know how to define it precisely.

Q: Have you ever heard it used?

A: Yeah, I have heard it used.

Q: What was the context that you’ve heard it used?

A: I don’t recall.[17](p. 160)

Q: What’s the most powerful piece of disconfirming evidence that you’re aware of for the theory that people can repress memories or that they can block out of their awareness a series of traumatic events, store those in their memory, and recover those with some accuracy years later?

A: What’s the strongest thing against that?

Q: Yes. What’s the strongest piece of disconfirming evidence?

A: I really can’t think of any good evidence against that.[17](p. 165)

Q: In your mind what’s the distinction between pseudoscience and science?

A: I’m sorry, that’s not something I think about.[17](p. 174)

Q: Now, when you were collecting data for the study on Dissociation and the Fragmentary Nature of Traumatic Memories, did you encounter a woman who had been molested by a grandfather who had a glass eye?

A: Yes, I did.

Q: Did you describe this case in considerable detail in your presentation at the 1994 American Psychiatric Association meeting in a symposium on trauma and memory?

A: If you say I did, I probably did.

Q: Do you have any memory of doing that?

A: I’ve presented it in a number of different settings, and it’s quite possible I presented it there, yes.

Q: So that wouldn’t be a dissociated memory, then.

A: No, if you say that I did, I’ll take your word for it.

Q: Now, at the conclusion of your presentation there do you remember describing how the patient and mother went to the grandfather’s grave and placed black roses on the grave?

A: I do, right.

Q: Is that a real or a false memory?

A: Well, since it only happened six months before I met her that she did it, and since she was an executive in a local Boston computer company, she was obviously very bright and with it, I never doubted that that story was true.

Q: So, then, you believe that the woman was molested, later recovered the memory, and went to the place — and then went to place the black roses on the grave with her mother?

A: I do. I do.

Q: Do you believe that there is such a thing as a black rose?

A: I was actually somewhat skeptical about it when I heard about it, but she told me so.

Q: What if I told you it was genetically impossible to produce a black rose?

A: Then I would say she probably planted a very dark rose on the grave of her grandfather.[17](p. 189-191)

They will not go to you and say, to me as a psychiatrist they will not say, “I now remember that I was molested.” They will always come to us and say, “I am going crazy. I am seeing things that are crazy. This cannot possibly have happened to me.” That’s one of the core things is that part of this whole trauma issue is that nobody wants to believe it has really happened to them. Nobody wants to believe that they got raped or that there was a gang bang going on or that their fathers who were supposed to love them took advantage of them, molested them. […] What is striking to us is the reluctance with which people recall these traumatic memories.[9]

We now know [PTSD and Dissociative Identity Disorder] are basically the same.[citation needed]

See also

References

[1] ^ a b Van der Kolk, B. A. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

[2] ^ a b Van der Kolk, Bessel A. (1994). “The body keeps the score: Memory and the evolving psychobiology of posttraumatic stress.” Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1(5): 253–265.

[3] ^ a b “Honors, Positions, Education.” Bessel van der Kolk. Archived from the original on 2021-11-02.

[4] ^ a b Bessel van der Kolk. Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bessel_van_der_Kolk on 2021-11-02.

[5] ^ “Biography.” Bessel van der Kolk. Archived from the original on 2021-11-02.

[6] ^ Kluft, R. P. (1991) “Editorial: reading notes.” Dissociation. 4(2): 63-64.

[7] ^ Contents (1988). Dissociation. 1(1).

[8] ^ Contents (1997). Dissociation. 10(4).

[9] ^ a b “Trauma and Memory.” (1993). Cavalcade Productions.

[10] ^ a b c d e Mesner, Doug (26 September 2011). “Bessel van der Kolk & the Disappearing Coauthor.” Dysgenics Report. Archived from the original on 2021-11-02.

[11] ^ McNally, R. J. (2005). “Debunking myths about trauma and memory.” The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 50(13): 817-822.

[12] ^ Dept. of Health and Human Services (1996). Released under the Freedom of Information Act on 2021-08-23. [Response letter, part 1, part 2, part 3.]

[13] ^ Dept. of Health and Human Services (26 April 1996). “NIH Guide: Findings of Scientific Misconduct, Volume 25, Number 13.” Archived from the original on 2021-11-02.

[14] ^ Van der Kolk, B. A., Fisler, R. (1995). “Dissociation and the fragmentary nature of traumatic memories: Overview and exploratory study.” Journal of Traumatic Stress. 8(4): 505–525.

[15] ^ “True/Not True.” (1993). Cavalcade Productions.

[16] ^ a b c d e f g h i j Deposition of Bessel van der Kolk in the Hungerford case. February 14, 1995.

[17] ^ a b c d e f g h i Deposition of Bessel van der Kolk in the Stevenson case. December 27-28, 1996. [p. 1-53, p. 53-74, p. 74-142, p. 142-229, p. 229-331, p. 331-371.]

[18] ^ Various documents, January 27, 1997 – February 24, 1997.

[19] ^ Complaint and Demand for Trial by Jury. Barnstable Superior Court, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Docket no. 98-425. March 03, 2004.

[20] ^ a b c d e f g Deposition of Bessel van der Kolk in the Archdiocese of Cincinnati et al case. March 16, 2005. [p. 0, p. 1-50, p. 50-104, p. 104-152, p. 153-186.]

[21] ^ Board of Registration in Medicine, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (03 April 2008). Records released under Massachusetts Public Records Law.

[22] ^ McKinley, James C. (28 May 2015). “Gigi Jordan Receives 18-Year Sentence for Killing Her Son.” The New York Times. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

[23] ^ Kowalczyk, Liz (07 March 2018). “Allegations of Employee Mistreatment Roil Renowned Brookline Trauma Center.” The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

[24] ^ Greenfield, Beth (13 March 2018). “Famed trauma therapist responds to allegations of bullying: ‘It’s an outrageous story.'” Yahoo!. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

[25] ^ Excerpts from depositions of Bessel van der Kolk, M.D. February 12, 1998. False Memory Syndrome Foundation. Boston, MA.

[26] ^ Labbe, Theola S. (17 October 1999). “Albany Psychiatrist speaks on the effects of childhood sexual abuse.” Times Union.

[27] ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Testimony of Dr. van der Kolk. August 2, 1996. Third Judicial District Court for Salt Lake County, State of Utah. Case No. 94-0901779-PI.

Documents

Last updated: March 26, 2023. Have more information to add or want to suggest an edit? Please contact us.